Oct 12

Prokofiev’s ‘The Gambler’ – director Peter Sellars makes a winning bet

Tim Pfaff READ TIME: 1 MIN.

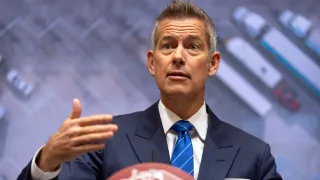

When the Salzburg festival mounted a production of Sergei Prokofiev’s “The Gambler” in 2024, it wasn’t the usual gamble. Audiences don’t flock to the composer’s operas because they’re grim, often surrealistic, and the music is unruly, spiky, and hard on the ears. Peter Sellars, the out director with spiky hair whose ideas once seemed radical, staged the production in a deft balance of naturalistic acting and surreal stage pictures, and it worked splendidly.

The Peter Principle

I say that with a kind of relief, of something like joy. Any director with Sellars’ now-lengthy history is bound to have some productions that are ringers. But he’s never been down for the count in the sense that his even most questionable work is often offset by manifestations of his directorial efforts that don’t just stoke memories of the “original” Sellars, but rise to their heights and beyond.

I count myself a veteran Sellars observer, going back to his revolutionary production of the three Mozart-Da Ponte operas at SUNY Purchase. “Don Giovanni” went first, only to be revised when all three took the stage. “Cosi fan tutte” decisively buried the notion of the piece as a comedy of manners. Sellars’ was a deep dive into the deep psychologies of the characters, complex and replete with their self-delusion, and it’s not an exaggeration to say that it changed my life, not just my take on the opera.

Trouble came with “Le Nozze di Figaro,” which Sellars set in Trump Tower, to no visible advantage. The press room afterwards was crowded with baffled commentators. It’s safe to say that that particular “update” –a signature Sellars move– was a misfire. But the music held up.

The strongest testament of my love for what now can be called “early” Sellars was a production of Wagner’s “Tannhäuser” at the Chicago Lyric Opera. The update was to the world of present-day televangelists, which was brilliant and absorbing. After reviewing the premiere, I flew back to Chicago for a second scoop.

A WFMT radio host provided an anecdote that perfectly captured Sellars’ directorial style. The company had allotted two hours for a staging rehearsal of the chorus, something that is usually its own drama, what with the heavy blocking and some bedlam. As the company officials watched in horror, Sellars used the two hours to telling the choristers who their unnamed characters were, nothing more, and when they took to the stage, they did indeed move naturally and left no doubt that the many members of the amplified chorus were credible individuals.

The production was, in its way, true, and there was little of the imposed movements, somewhere between the gestures of Japanese Butoh and hieroglyphics, that were an early Sellars signature. Though these theatrical impositions have returned to haunt later productions, they’ve matured and become more believable and expressive in a way not geared to maximal audience perplexity.

What’s become clear over the decades is that Sellars’ hits are as good as the music they set. Note the difference, say, between the (enacted) Bach’s “St. Matthew Passion” and John Adams’ lark, “The Girls of the Golden West.”

Some directors have what amounts to their own staging team. The set designer George Tyspin and lighting designer James F. Ingalls have been with Sellars from the beginning, their loyalty a tribute to the director’s deeply considered style.

A gamble worth taking

Sellars and his team have concocted a staging that is an ideal setting for Prokofiev’s relentless, wild music and his complete surrender to the terms of the Dostoyevsky’s short story on which it is based, with its grinding, unsparing depiction of the denegrations of addiction. Prokofiev wrote his own libretto.

With the full resources of the Salzburg Festival at their disposal, they transform what is basically a unit set into well-defined playing spaces. In the DVD, there are both closeups and scenes viewed from above. But what gets the attention is Tsypin’s realization of the score’s corrosive, expressionist qualities.

Ingalls lights it all with dizzying layers of colors, slabs of primary colors, often overlapping, to create an environment of menace and, you could say, bad luck. With the Vienna Philharmonic in the pit, Timur Tangiev could, and did, go for broke, and the spiky, often discordant music of the opera kept the hectic drama front and center.

Few directors can match Sellars when it comes to the direction of characters. A production in which Asmik Grigorian, the finest singing actor on the boards today, as the story’s principle love interest, is not a stand-out among the cast of desperate figures is a dream ensemble.

Grigorian is brilliant as Polina, but what’s telling here is that she’s as compelling when not singing than when she tugs at the heart with her voice, deploying it here with what is almost an inattention to standard vocal manners.

As her emotionally unstable partner –true love is compromised by the inconvenience that Polina owes the scheming Marquis money– Sean Pannikar is outstanding as Alexey. His mastery in capturing the character’s lability –he adds the occasional grimace of a smile to the arc of his descent– is rendered in a tenor of enormous range, musically and dramatically. He’s the center of this play, and he gets the opera’s best single line: “Money is everything.”

Also outstanding in this company of equals is the veteran mezzo-soprano Violetta Urmana as the grandmother from hell. She dodges her son’s petition for money (she has lots) by losing her entire fortune at the roulette wheel.

High stakes

Prokofiev’s fidelity to Dostoevsky’s story turns the whole of the stage play into a harrowing parable of addiction and its horrors. Alexy is not the only character brought down by it, but his fruitless pursuit of both fortune and love trace the unyielding power of the former over the latter. It’s his reduction to defeated impotence that we watch like a car wreck, unable to turn away.

Addiction experts consider gambling the most intractable of them, and this cocktail of Dostoyevsky, Prokofiev and Sellars, with the latter’s thoroughly uncompromising direction, results in a fable that is hard to take and harder to shake. It does the comparable plot of “The Queen of Spades,”with Gemann’s fatal gambling addiction, one better.

Don’t count on seeing fully staged Prokofiev operas on the stage. They’re relentlessly dark and hard to grasp on first hearing. But in its 2023 Opera Festival, the Bavarian State Opera’s annual opera mounted a production of his “War and Peace,” a long, sprawling opera answering the demands of Tolstoy’s famous novel. It was performed at San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House in the 1991 season.

Cast with largely Russian singers (and the company debut of Valery Gergiev as conductor), it fell at the same time the Soviet Union disintegrated, and, when not rehearsing on stage, the singers were hunkered down with television coverage, even in the wings. It was a high-water achievement for the company.

The Bavarians turned to director Dmitri Tchneriakov, whose work, like Sellars’, is hit and miss but a guilty pleasure of mine, also as good as the score in front of him. Going with Vladimir Jurowski as conductor stabilized and enlightened this must-see production.

Sergei Prokofiev, “The Gambler,” 2024 Salzburg Festival, Peter Sellars, staging, Timur Zangiev, conductor, Vienna Philharmonic, Unitel.

https://www.europadisc.co.uk/

Sergei Prokofiev, “War and Peace,” Dmitri Tcherniakov, director, Vladimir Jurowsky, conductor, Bayerische Staatsopera, 2 DVDs, Unitel.

https://www.naxos.com/